Can you alter historic architecture without changing its character?

Whimsical 1931 Colonial asked us to put aside ego and honor the architects’ intent

We don’t build things like we used to.

One hundred years ago, builders just knew how to use tools, materials and plans, perhaps in a way that few remember how to now. We could argue about whether the old way of building was better. But when we find great buildings, a century old, still structurally sound like the day they were raised, that speaks for itself.

A client recently asked Studio KLP to make alterations to a 1931 Colonial-style home in Northeast Pennsylvania. It had been designed by the prolific and influential Wilkes-Barre architects Donald F. Innes and Charles L. Levy. Their work primarily centered on stately homes; their portfolio includes local elites with names like Nesbitt and Kirby. The duo also served as architects of record for the Fox Hill Country Club and a tuberculosis sanitarium in Drums.

Their trademark country projects dot the hills surrounding the Valley. There’s something fantastic about their projects. They’re stately, commanding with a touch of whimsy. They popularized the Tudor Revival in Northeast Pennsylvania, and designed much of the City of Wilkes-Barre’s River Street historic district.

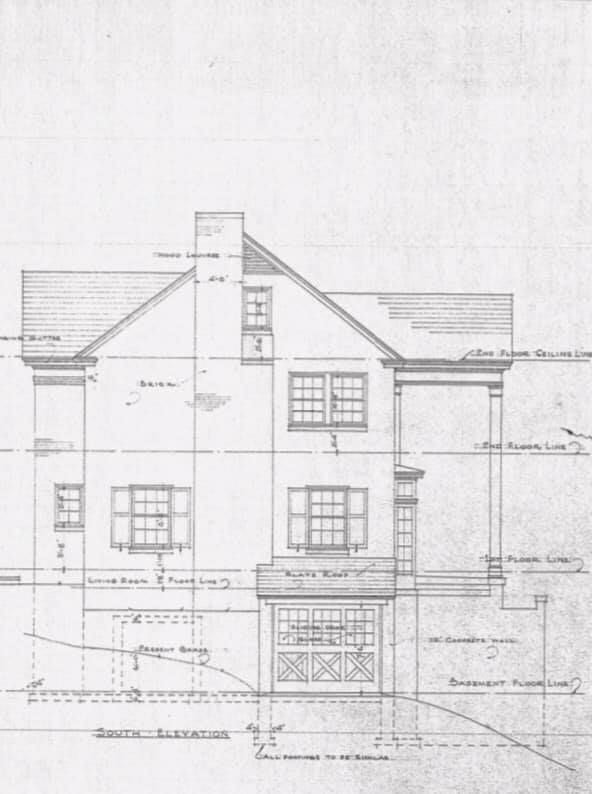

When WLK got the job, we found original plans that were simple and uninvolved by today’s standards, like the difference between a roadmap and a GPS screen on your dashboard.

The client teased and said, “you’d have a stack of drawings this high!”

The roof note simply says “slate roof.” For comparison, when Studio KLP oversaw a big new slate roof in 2007, we brought in a specialist from Colorado to teach the entire team how to do it; we had three pages of drawings just for the roof assemblies.

This vocabulary in the drawings is restrained and on its face conventional, but it is more than that; it is erudite, not necessarily cutting-edge but very skilled in its massing, detailing and response to the landscape — as taut as a well-crafted song.

Now comes the conundrum. Like any artist or creative, architects all have their own brand. The most successful architects have a trademark look that receives a large enough consensus of approval. Everyone in this craft, unless they utterly lack ambition, aims for that. Ego boils beneath the surface, in search of a vent. The 1931 Colonial could offer no such vent. It begged for, or perhaps demanded, respect and preservation of spirit.

Knowing how to feel a culture not of one’s own is a beginning. You work to acquire the vocabulary in rigorous efforts like this, then you can learn to speak it in your own contemporary work. A project like this is like practicing Stravinsky on the piano over and over. First you learn the words that connect design to humanity, then you speak that language in your own voice, if you’re lucky.

We hardly know how to think like they did. The Colonial had a Juliet balcony next to the chimney. What’s it about? Pure romance, no doubt.

Projects like these ask the architect to become the historian. The gatekeeper and treasurer of what happened once, but no longer does.

It would be easy enough to reinterpret the original architects’ intent for a contemporary audience; and plenty of great restorative architecture does that.

That wasn’t our job here. Instead, we needed to be more like archeologists than architects. We didn’t get to tell the story. Instead, we had to just ensure the same story could be told again.